With the start of the second Trump administration two months away, the top questions I am hearing from practitioners across the country continue to be variations of: “what will the next four years hold for economic development programs?” There are no definitive answers to be had, but we can learn a lot by reviewing the record of the first administration and what has been proposed for next one. This is a topic worth addressing from multiple lenses, but for now, let’s look at what may be ahead for the Department of Commerce.

Department of Commerce

During the previous Trump administration, Wilbur Ross was Secretary of Commerce for the entire term. The transition is yet to name a nominee for the next administration. Linda McMahon, who led the Small Business Administration during the first term and is a co-chair of the transition, is widely seen as a likely pick to lead Commerce this time around.

[Edit 11/19/24] The Trump transition has announced its other co-chair, Howard Lutnick, as the nominee for Secretary of Commerce. Lutnick is CEO of Cantor Fitzgerald and does not have much of a policy or government record to search for indications for his Commerce priorities, although he has been a vocal proponent of enacting tariffs and reducing government spending. Trump stated that Lutnick will also have “direct responsibility” for the U.S. Trade Representative, which is currently part of the Executive Office of the President.

The Trump campaign and Republican party platform are largely silent on priorities for Commerce, but the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 has numerous proposals. Project 2025’s chapter on the Department of Commerce is authored by Thomas Gilman, who served as the department’s CFO and Assistant Secretary for Administration under the first Trump administration. (Not sure if Project 2025 is relevant: read why I’m paying attention to it, below.)

Consistent with the first administration’s budget proposals, which were acknowledged to be largely developed with Heritage Foundation input, the chapter focuses on Commerce’s overlaps with other departments. Gilman encourages a government-wide review, perhaps an activity Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy plan to undertake, to have an eye toward, “consolidation, elimination, or privatization.” In brief, Project 2025 is recommending a smaller Commerce that places more emphasis on resources and (de)regulation than programs.

Economic Development Administration

During the previous Trump term, the administration regularly proposed defunding EDA. The agency had one Senate-confirmed leader, John Fleming, and he only served from March 2019-March 2020. Under the previous administration, EDA investment priorities included infrastructure and Opportunity Zones, which were replaced by the Biden administration’s preferences for equity and sustainable development.

Consistent with the Heritage Foundation’s record, Project 2025 makes to clear that its preference is to eliminate EDA. However, in recognition of past failures on this point, Gilman proposes a pivot: centralizing decision making in DC.

Under a centralized approach, EDA leadership would control more of the grantmaking and emphasize “conservative political purposes,” which include funding rural communities. Other priorities for the agency would include “building on the initial success of Opportunity Zones” and continuing with disaster funding. Administratively, the proposals emphasize downsizing career employees and using contracts to supplement staffing needs.

The impact of these proposals for EDA’s innovation programs is uncertain, as none are called out explicitly, but Project 2025’s vision indicates a hands-on approach for the next Assistant Secretary. EDA’s Office of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (which includes Build to Scale and STEM Talent Challenge) and the Tech Hubs program are already administered in EDA’s DC office. Forthcoming notices of funding from these programs could easily emphasize the administration’s revised investment priorities.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

During the first Trump administration, Walter Copan was the NIST director for the entire term. One of Copan’s major efforts, which aligned with the White House’s management agenda, was the Return on Investment (ROI) initiative, encapsulated in a 2018 green paper. The ROI initiative aimed for more effective and efficient processes for converting innovations from government labs to the commercial markets (e.g., technology transfer). Specific proposals included expanding use of partnership agreements, reforming the “government works” exception to copyright protections for software, and better-defining march-in rights. The Biden administration’s attempt to address march-in rights has been controversial.

Project 2025 calls on NIST to “reinvigorate” its efforts on the ROI initiative.

Otherwise, the Mandate for Leadership’s proposals for NIST emphasize privatization. Gilman calls for the Manufacturing Extension Partnership to be eliminated as a federal program, with that work to instead be conducted by the private sector, and makes a similar call for the Baldridge Performance Excellence Program. The Manufacturing USA centers receive no explicit mention in the chapter, but with their initial (and extremely unlikely) vision for only short-term federal funding, it is likely that the Heritage Foundation would also favor privatization for the centers.

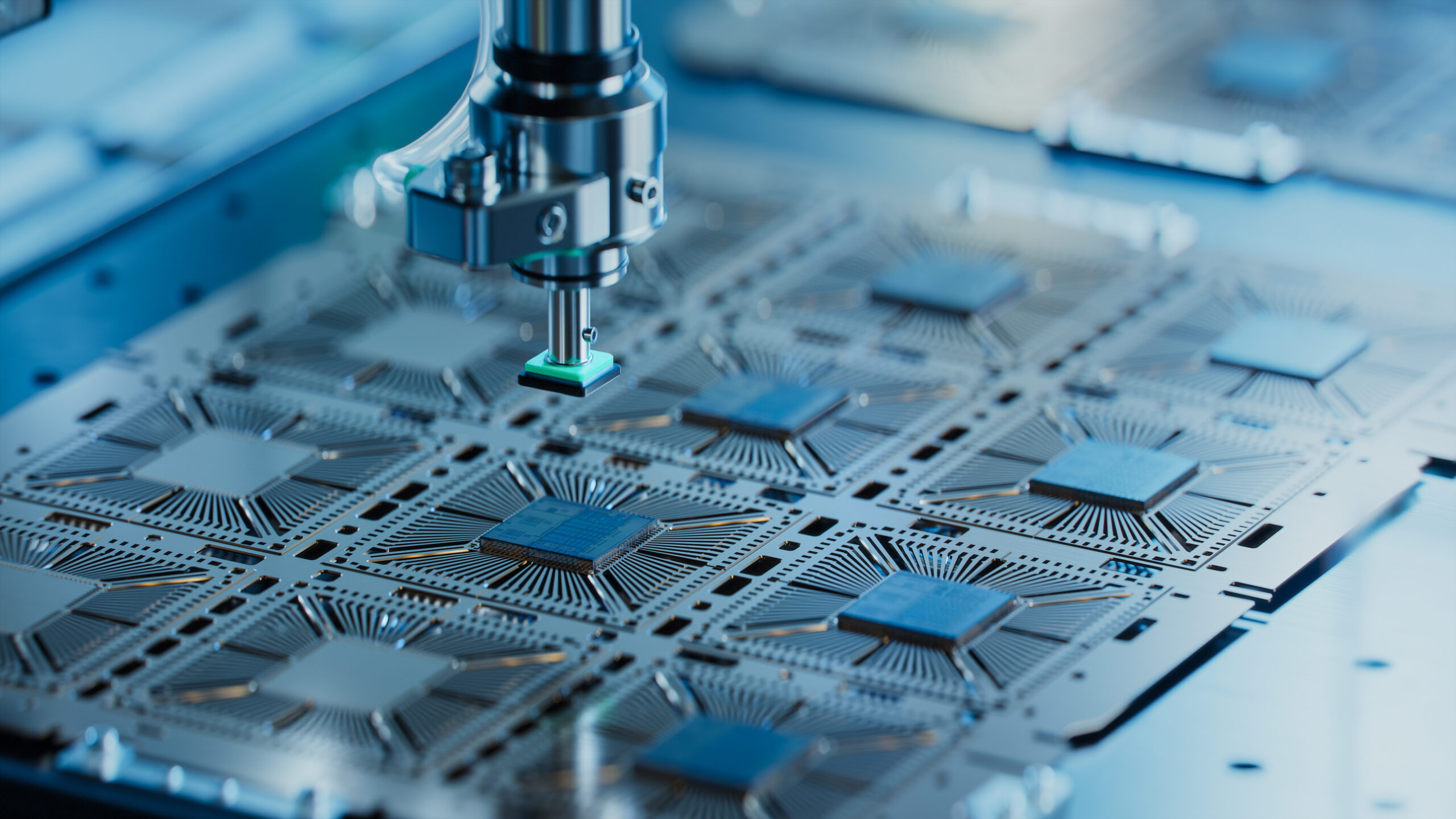

Conspicuously absent from Project 2025’s proposals is the semiconductor funding and other elements of the CHIPS and Science Act. This has been a major area of emphasis for NIST in recent years and has bipartisan support. While Project 2025 does not suggest what the administration’s approach should be, the Heritage Foundation itself has had plenty to say about semiconductor incentives. The summary of their perspective is that while America needs to develop a domestic chips production industry, this should be accomplished through deregulation, not funding.

There can be little doubt that the next Commerce Secretary and NIST director will exercise influence over semiconductor funding, but it is impossible to know what this will look like until we hear from the relevant personally and then see how Congress responds. In addition to the Heritage Foundation’s opposition, Trump and Mike Johnson both made comments against semiconductor funding in the closing weeks of the campaign. However, Johnson walked his statement back, his staff have reconfirmed that he supports CHIPS, and other Republicans, including incoming Vice President JD Vance, have supported the funding. Still, the next administration may change how the CHIPS funding is implemented.

Other Commerce agencies

Consistent with the first Trump administration’s operations and proposed budgets, Project 2025 advocates for eliminating or restructuring much of the rest of the Department of Commerce. Specific suggestions from its publication include the following:

- Transforming the Minority Business Development Agency from a grantmaking body into an agency that simply provides data and information (and only this because Gilman does not believe Congress would support eliminating the agency at this time)

- Dismantling the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration by moving some of its functions to performance-based organizations and distributing the rest across other agencies

- Making the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office a performance-based organization under the White House Office of Management and Budget

What to watch

The key areas to watch for signs of the administration’s plans—and actual actions—are (a) who is nominated for secretary, (b) how a “department of government efficiency” proceeds with government-wide reform actions, and (c) what signals Congress provides about its willingness to support the department.

Some additional context on this last point: from 2017-2020, Congress was unwilling to support many of the Commerce budget proposals advanced by the first Trump administration. EDA programs, for example, fared well despite recommendations for their elimination. Current signs suggest that members of Congress may need to stand up again, or at least provide their own proposals for reform, if they wish to continue to see a Department of Commerce that is able to continue achieving any of the impacts on technology and the economy that we’ve come to expect.

What to do

Practitioners who want to support Commerce programs should prepare to both defend existing initiatives and propose changes that could strengthen outcomes, particularly for the next administration’s priorities. This is basic advice, but that is all too easy to lose sight of during periods of major change.

More specifically, technology and economic development organizations should be preparing the following:

- Information on the impacts of existing programs/awards. Yes, data matters and you need it. You should also have a few stories that clearly show how project activities support private companies and workers.

- Strategy to communicate program priorities to Congress. Even if sympathetic personnel are placed in charge of key Commerce initiatives, administration proposals to eliminate agencies or programs may block those staff from supporting the programs. You need to ensure Congress knows what programs matter to constituents and what needs done to preserve their impacts.

- Development plans for other sources of funding. There is no need to write off Commerce programs as a source of funding at this point, but organizations should be prepared for possible disruptions. The best way to support your region is not only to advocate for the programs in Washington, but also to make your initiatives financially sustainable without federal funds.

Why Project 2025 matters

The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025—or, more specifically, its voluminous Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise publication—became a lightning rod in the 2024 presidential election. While the Trump campaign distanced itself from Project 2025, the initiative’s connection to the transition team has been another story. Brendan Carr, nominated to chair the Federal Communications Commission, wrote the Mandate for Leadership chapter on the FCC, and two other high-profile selections, Tom Homan and John Ratcliffe, are listed as contributors. Project 2025 won’t have a lock on the next administration’s policy, but as an unnamed Heritage Foundation official bragged to Politico, “we’re so back.”